Higher Critical Method–An Introduction

For hundreds of years, intelligent and rational scholars have wrestled with these very issues. They have put together a series of rules and guidelines to help us more accurately interpret scripture so that we can find spiritual truths by “reading out” the meanings recorded in scriptures rather than “reading in” our preconceived values and perspectives. In this way, our modern task is to find timeless truths in scripture that are informed by our current life, times, and world view.

This process, often called “Higher Critical Method” or “Historical Critical Method” has a number of tools and techniques to help us get to the “true gold” of a scriptural passage while tossing aside the cultural and historical dross which makes no sense and only distracts us from our goals:

Textual Criticism

Those who believe in scriptural inerrancy will say that only the Hebrew or Christian scriptures in their original text is without error–or something to that effect. But what are these original texts?

Jewish Textual Challenges

For Jews, the entire collection of canonical scriptures is called the Tanakh. The authoritative Tanakh for Rabbis dates to the 7th to 10th century CE, almost 2 millenia after it was first recorded. It is called the “Masoretic Text.” The oldest complete copy of the Masoretic Text dates from the 11th century CE when it was found in St. Petersburg, Russia.

The Samaritans were a mixed people comprised of Jews who inter-married with other races following Assyrian’s capture of Israel in 722 BCE. Their scripture consists of only the first 5 books of the Tanakh, known as the Torah or “Law.” The “Navi’im” or “Books of the Prophets” and the Kithuvim or “Writings” which make up the Hebrew or Jewish scriptures today were not seen as “Holy Scripture” by the Samaritans. However, even comparing only the Samaritan Torah with the Masoretic Torah reveals some 6,000 differences in the two texts.

Older passages of some portions of the Tanakh can be found in the Dead Sea Scrolls (dating from about 3 BCE to 1 CE. A Syriac translation dates to 2 CE. As the diaspora of the Jewish people continued in the Hellenistic era, a Greek version of the Hebrew scriptures was translated in the 3rd century BCE. Known as the Septuagint, it allowed Jews to maintain their faith as they learned the lingua franca of their day and didn’t always remain connected with a Hebrew community. In approximately a third of the 6,000 discrepancies between the Samaritan and Masoretic Torahs, the Septuagint agrees with the Samaritan version.

Anyone who has ever worked with translated documents knows how hard it is to translate a clear, unambiguous thought from one language to another. When required for international treaties or multilingual laws, one set of translators translate from the source language to the target, and then have a different set of translators convert from the target back to source to assure the accuracy of their work. As an example, the Masoretic text for Isaiah 7.14 reads, “The Lord himself [sic] will give you a sign. Look, the young woman is with child and shall bear a son, and shall name him Immanuel.” However, the Septuagint translates “young woman” as “virgin”. Later in the Christian era, the writer of the Gospel of Matthew uses this Greek translation to support the claim that Jesus was born of a virgin (Mt. 1.23). It is a claim that could not be supported if the Masoretic text was the only authoritative version in the 1st century CE.

Christian Textual Challenges

Although Christian gospels, histories, and letters becan to circulate, be copied, and widely shared within a century of the life of Jesus, Christian groups have no less of a challenge. Early letters were written to encourage and embolden other local faith communities. There is no indication that they were seen as sacred writings yet. There was no printing press, no photocopiers, and no trained profession of scribes who fascidiously copied each document over and over. As a result, there are literally thousands of copies of early Christian writings but most of the early copies did not survive the centuries. They are generally broken into three groups:

- Uncials or Codices: These are sections of scripture written in capital Greek letters and generally contain large collections of documents. Usually they were written on parchment or velum and are well preserved. There are over 300 uncials dating from the 4th to 11th centuries CE.

- Miniscules: Miniscules were written in small (lower case) Greek letters and were mostly written on parchment. They tend to date from the 9th century CE or newer. There are over 3,000 miniscules in existence.

- Papyri: Papyri, as the name infers, were written on a paper made from a type of paper produced by mashing up the Egyptian papyrus plant. These include the oldest copies of scripture, some dating to within a century of Jesus’ life. However, papyrus was not very durable. It easily decayed, wore out, or was eaten by animals and insects. There are only about 140 papyri fragments ever found and most only include the text of no more than a few verses of scripture and few are even a full width of a line of text.

An example

For example, the Gospel of Mark has 3 different endings. The most likely original ending concludes at Mark 16:8a:

As they entered the tomb, they saw a young man, dressed in a white robe, sitting on the right side; and they were alarmed. But he said to them, “Do not be alarmed; you are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has been raised; he is not here. Look, there is the place they laid him. But go, tell his disciples and Peter that he is going ahead of you to Galilee; there you will see him, just as he told you.” So they went out and fled from the tomb. (Mk 16:5-8a)

It seems consistent with the author’s entire narrative: even when Jesus performs the most amazing miracles, nobody seems to “get” what Jesus is about. Here is the story of the resurrection, but the women are “alarmed” and just flee the tomb. The author perhaps doesn’t know anything more, or wants the reader to ask him or herself what they would do in the same situation.

But for many, it is an unsatisfactory ending. This led to the theory that an early scribe tried to “wordsmith” verse 8 to read (rather awkwardly):

So they went out and fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.

You might say that we already know this: of course they fled because they were afraid and in terror. It’s kind of like saying, “They acted terrified because they were.” But this added ending goes on with another sentence that completely undoes the first part of verse 8:

And all that had been commanded them they told briefly to those around Peter. And afterward Jesus himself sent out through them, from east to west, the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation.

So here we finally have a “happy ending” to Mark. It softens the ending of the Gospel by replacing the terror and fear of the women with their sharing the news and being dutiful servants proclaiming salvation from east to west.

Still later, another ending was added: verses 9-20. These verses are not usually included in biblical texts or might only be included in a footnote under the text. There are significant linguistic and stylistic differents in these 11 verses from the rest of the Gospel. Scholars generally date this extended ending to the early 2nd century CE even though the rest of Mark is regarded as the first Gospel to be written down.

Rules to Use in Textual Criticism

Scholars spend their career trying to determine which is the most original text of any given passage. For the rest of us, we can use some guidelines to help us out:

- Older translations of scriptures do not have the benefit of more recent research. The King James Bible, which was translated in 1511 CE is probably the best example of a bible to avoid as it makes no use of the last 400 years of scriptural research. The New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) is one of the newest scholarly translations and was first published in 1989.

- Get a good study bible that offers footnotes or comments of alternative possible textual options. The New Oxford Annotated Bible is one such study bible and is available in NRSV.

- Generally versions with shorter passages are preferred to longer passages. Scribes were likely to add more words or explanation to a passage as an aid to the reader rather than remove words from their own copy. An example is Mk 16.9-20. This ending to the Gospel of Mark seems to have been added in the 2nd century CE because the original gospel ending was too sharp and short and didn’t offer readers a happy ending.

- More difficult versions and translations are likely more original. Scribes are morely likely to rearrange word order to make passages more readable or palatable to readers.

- Versions that instill dissonance are preferred over ones that gloss over difficulties in doctrine or practice.

- Older versions are preferred.

- Versions that have been used to produce the most next generations of copies are preferred.

Of course there are many more examples where Textual Criticism can help us more accurately discern the original text of our Schriptures. The above examples are simply to illustrate the point. This is after all just a primer or introduction to the concept.

Source Criticism

Almost no scriptural accounts can be traced to first-degree sources. There was no journalist on the scene when Moses parted the waters of the Reed (or Red) Sea. No historian collected verbatim eye-witness accounts of the crucifixion. No fragments of the ten commandments have ever been found. In fact, in many cases, the claims of scripture and historical facts don’t agree. The Roman archives have no report of a “decree from Emperor Augustus that all the world should be registered” (Lk 2.1).So where did the scripture writers get their information?

Sources in the Jewish Scripture

The first five books of the Hebrew Scriptures, also known as the Torah, document the faith traditions of the Jews from pre-history until the colonization of what is modern day Palestine. If we look at these books closely, they have some puzzling sections.

For example, there are 2 creation stories, not one.

The first one has “God” very methodically creating everything in 6 days and resting on the 7th. That story ends with the writer saying, “So God blessed the seventh day and hallowed it, because on it God rested from all the workthat he had done in creation.” (Gn 2.4). In this story, the order of creation is one of creating order. Before creation there was only chaos which in the mind of the writer is a universe of water, or “the deep” (Gn 1.1). Order comes when god separates the water and puts it in its place: first god creates light so that the water can be lit up for the day and be dark during the night. Then god separates the water into oceans and clouds by putting a layer of atmosphere between them. Next god separates the oceans by allowing land to rise up. These are the first three days in the story. Only on the fourth day does god create the Sun and Moon–the very heavenly bodies which allow there to be day and night at all. Only on the last 2 days does god get around to creating life: birds and fish on day 5, and land animals including humans on day 6. The writer also uses the generic term for “god” in this story. That word in Hebrew is “Elohim.”

The second creation story begins in Gn 2.5. In that story, the Earth exists but starts out parched and barren. God makes man (in Hebrew “Adam”) first and then proceeds to plant a garden for the man to live in. At the end, god creates all the other animals and then realizes that he never made a sexual partner for the man and creates woman (in Hebrew “Adamah”). In this story the “Lord God” is the name used for god in most translations. But that word “Lord God” is actually the 4 Hebrew letters “YHWH.” This is such a holy name for god among Jews that most observant Jews never say this name out loud. If they do need to refer to it verbally, they replace it with “Adonai” meaning “Lord.”

So why such different stories? And why different names for god? These are questions that we can ask over and over again as we read through the books of the Torah.

Simply put, experts believe that more than one tradition was merged into the modern day Hebrew canon. The second story, which is probably the older one, was a folk myth dating from the earliest period in Israel’s history. It’s not meant to be a historical account. It’s key message includes:

- Humans are special, that human sexuality is a gift to us from god, and that men and women have an equality, and together comprise human unity and completeness.

- The world around us was created to be good and a gift. It was after all “Eden.”

- Humans are naturally innocent and not ashamed of themselves but also have moral and custodial obligations in their relationships with the world, each other, and with god.

Scholars call this source the Jahwist, or J tradition. The use of YHWH as the name for god is a flag that we are reading a story from J.

Scholars believe that all these stories were put together after 587 BCE when the Jews were conquered by Babylon and exiled from their homeland. Priests took these stories and packaged them into the canon we have today but not before filling in the gaps they felt were important for the Jews to remember. One of the most important Priestly concerns was that people remember the Sabbath (or 7th day) and keep it holy. So they included their own story of creation that emphasized this point while amplifying the J tradition that creation was good, and that humans were special. P wasn’t trying to write a historical account either. To prevent the risk of someone saying the name YHWH out loud, they just the word for “god”. The use of the name “God” alone is a good clue that you’re reading a story from the Priestly or P source.

Sources in Christian Scripture

In the Christian bible, there are four “gospels” or stories of the life of Jesus: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. John’s gospel is quite unlike the other three. Its language, imagery, and even order of stories differ from the others. In some cases it contains stories that the other three gospels don’t even have (like the conversation with the Samaritan woman at the well in Chapter 4). Sometimes it omits stories that are in the other gospels.

If we set the other three gospels side-by-side based on their similarities, we find that Matthew, Mark, and Luke contain the same stories–often verbatim–as each other. The table below shows one small example of this. The text highlighted in yellow shows the identical wording between these three gospels and the most similar story from John’s gospel in the fourth column.

A synoptic comparison of (left to right) Mt 21-23-27, Mk 11.28-33, Lk 20.2-8, and Jn 2.19-25. These texts are from the New International Version of the bible, an older translation which is less inclusive in its language. However, it does highlight identical language in yellow across the 4 gospels.

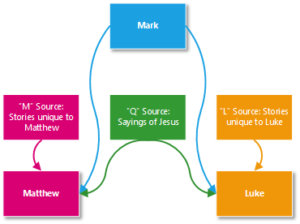

This raises an interesting fact about the first three gospels, often called the “Synoptic Gospels” because they tend to see the story of Jesus in the same way. Mark is the oldest of the four gospels we have in our bibles. In fact, Mark’s Gospel was likely already in circulation at the time that Matthew and Luke wrote their gospels. Like a student writing a term paper, they probably used Mark’s gospel as one of their research sources as they each sought to tell their own story. But it wasn’t their only source.

The sources used by the Gospel writers of Matthew, Mark and Luke.

Matthew and Luke also seemed to have a source of many of the sayings and quotations of Jesus. This source, called “Q” by scholars includes the story of Jesus temptation following his baptism; Mark and John do not record any mention of the temptation. Q also includes the Lord’s Prayer, the Beatitudes, and many other sayings of Jesus.

While Mark and John have no record of the birth of Jesus, Matthew and Luke have very different stories. Luke’s infant narrative is pretty much the one we celebrate at Christmas: following a decree for a census from the Emperor, Joseph takes his wife and they leave Nazareth and go to Bethlehem. Once there, Mary gives birth in a manger. Mary was a virgin. There is no star over Bethlehem and no wise men from the East.There are shepherds and and an angel choir. Once the birth is over, Joseph and Mary head back home to Nazareth.

The star and wise men are from Matthew’s account. In that story, Joseph and Mary live in Bethlehem–they give birth to Jesus in their own home. The wise men complicate the story. The king is not happy to hear that there is a rival. He kills all the male children in Bethlehem and so Joseph and Mary flee not to Nazareth but become refugees in Egypt.There is a hint here that Mary might have been a virgin to fulfill prophesy, but it is not a key element of this story.

Why is this important? Imagine that you were an early first century Christian. Your community might have only had stories passed down through the oral tradition. If you had a written copy of a Gospel at all, you possibly only had a single copy of one of the gospels. Copying and distributing scripture took money, but mostly time. If your community had a copy of Mark or John, then you knew nothing of a “virgin birth” and this wouldn’t have been important to you anyway. If you had a copy of Matthew, your Christmas celebration would have been very different from those communities that had a copy of Luke. The sources that your community came to rely on filtered and taught you which stories of faith were the important ones. But the doctrines and stories that were told to you, and the ones you would retell to your children, would be a consequence of chance, and not one of divine providence.

Form Criticism

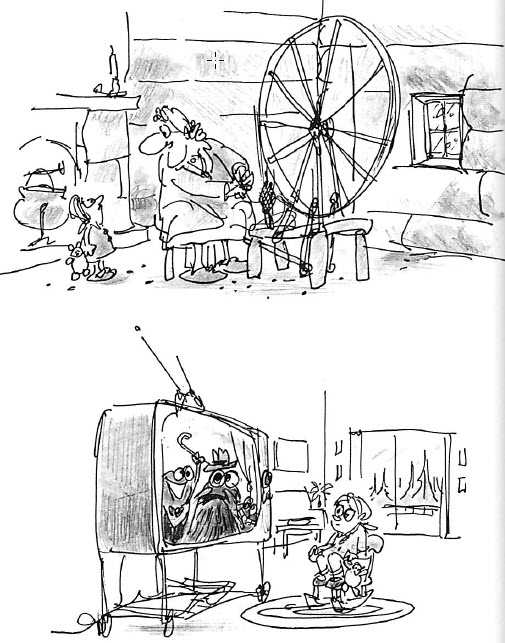

The literary genre fairy tale had its original setting in a now-vanished way of life. The wintertime spinning rooms of earlier centuries no longer exist. The new children’s “storyteller” is television.

Every culture has its own collection of literature. This collection often includes poetry, jokes and humour, and many different types of stories: fictional stories including epics and fairy tales; less-fictional stories such as biographies, battle stories, and historical accounts. Each type of literature is called a “genre” and each genre has a particular setting or place where it is used.

For people familiar with their own culture, they understand how to interpret a particular genre. For example, if a story begins, “Once upon a time in a land far, far away,” they know that this is a fairy tale. It is intended to amuse children and is not a true account of any actual event. It should just be enjoyed as a story.

If a story begins with, “A rabbi, a priest and a minister walk into a bar” we know that we should get ready for a joke. In just a few minutes, there will be a punchline after which we should laugh. It is as socially embarassing not to laugh at a joke as it is to tell an joke that is inappropriate for a particular audience.

We understand how to interpret genres because we grew up in the culture where they exist. Like so many things about culture, we just absorbed these facts as we grew up.

Still, it is possible to “misread” a particular genre. Satire is a form of comedy that can often appear as fact but is instead fictional. For example, there was a radio program in Canada called, “This is That.” It aired Saturday mornings and seemed to have the format of a “news magazine.” In fact, so many people were confused by the genre that the program got lots of angry mail from people who believed the stories to be true. One of my favourite stories was about a university student who was suing her university for not accomodating her “visual allergies.” While satirical stories aren’t “true”, they often serve the purpose of pointing out social norms and mores that warrant social discussion. In the case of the “visual allergies” story, the creators may be be questioning the extent that “political correctness” has taken over our society.

Even if a story isn’t “true”, it may still contain a “truth.” Aesop’s stories fit into this category. We all know about “The Hare and the Tortoise“. This is a sub-genre of Children’s Story and intended to help children learn to value dedication, tenacity and persistence. Even those the story is fictional, these values generally provide good life lessons.

Millenia ago, the writers of scripture–and the people listening to it being recited–understood these genres and how to interpret them. They didn’t necessarily see these stories as fact, but they understood the truth that they contained.

When a story began in the nominative case and launched its narrative without any preparation, hearers in the ancient Near East could asume with a certain confidence that they were about to hear a similitude.

Sadly, many religious leaders today have no understanding of these various literary forms and do a terrible job of helping their followers understand the point of these scriptural passages. For example, the story of the Good Samaritan (Lk 10.25ff) is a similitude. It appears to be an answer to the question, “who is my neighbour?” But the answer is in the form of an extreme comparison: Jewish robbers who beat up a fellow Jewish traveller and leave him “half dead” are clearly not good neighbours even though they share a common ethnicity and religious heritage–is compared with a Samaritan who stops to rescue the traveler, takes him to an inn, and pays for all his medical and living expenses out of his own pocket even though Samaritans are the sworn enemies of the Jews.

But if you take a tour of Israel today, your tour guide might have the bus stop at a roadside building while telling you that this is the actual “Inn of the Good Samaritan.” There is no actual inn. Similitudes are not factual stories in this sense. They are told only to illustrate a point.

Without understanding biblical literature, it’s impossible to understand the truth or message of scripture.

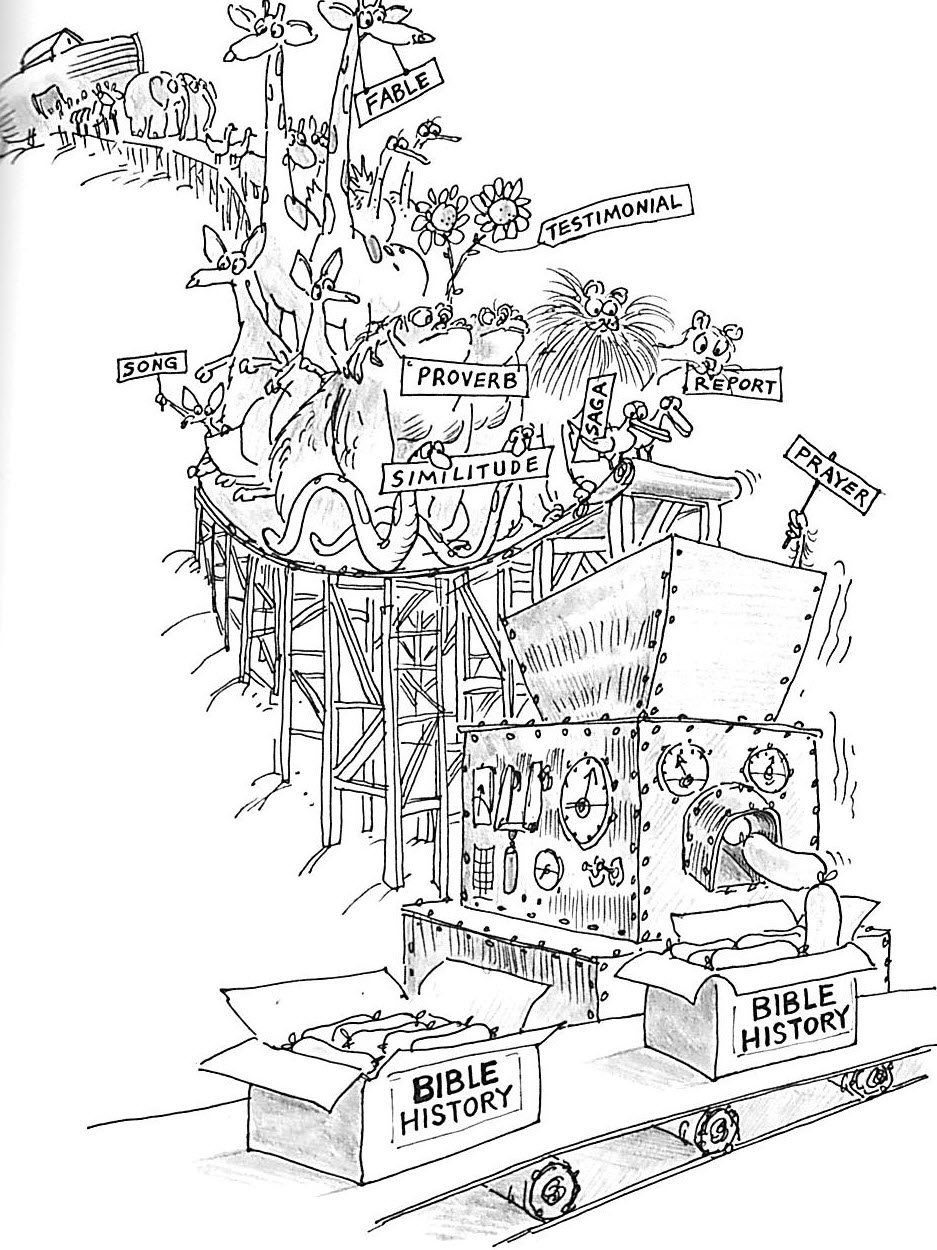

By not understanding the literary forms of scripture, many religious groups turn the bible into a fabrication that we call “Bible History.” As a result, they miss the point of the story by focusing on the wrong details. For example, instead of reading the creation narratives as stories of how wonderful our world is; literalists get bogged down in the belief that the earth is only 6,000 years old and then pick arguments with palentologists about how dinosaurs co-existed with people and carbon dating is all wrong.

Form criticism doesn’t mean that scripture isn’t true; in fact, just the opposite. It helps us to affirm exactly how various parts of scripture are true.

But it also refutes any claim that the bible must be literally true and inerrant. And this is a good thing as we seek to grow our own faith and affirm the humanity and spirituality of our neighbours.

Images on this page are taken from:

Gerhard Lohfink (illustrations by Bill Woodman)

1979 The Bible: Now I get it! Doubleday & Company. Garden City: New York.

With this short primer, most readers coming from a Jewish, Christian, or Muslim background should be able to have the necessary background to more critically engage in their own spiritual and scriptural traditions.

Our goal is not to refute anyone’s religious belief. But sometimes, dogma and belief becomes so rigid, entrenched, and self-reinforcing that there is no room for fresh air–let alone divine inspiration or spiritual revelation–to enter the dialog. By looking at scripture from a historical critical perspective, our tendency for arrogance and conceit might be curtailed, and our capacity for love and understanding might be enhanced and affirmed.